(Reuters) — As Britain’s COVID-19 infections soared in the spring, the government reached for what it hoped could be a game changer — a smartphone app that could automate some of the work of human contact tracers.

The origin of the NHS COVID-19 app goes back to a meeting on March 7, when three Oxford scientists met experts at NHSX, the technical arm of the U.K.’s health service. The scientists presented an analysis that concluded manual contact tracing alone couldn’t control the epidemic.

“Given the infectiousness of SARS-CoV-2 and the high proportion of transmissions from presymptomatic individuals, controlling the epidemic by manual contact tracing is infeasible,” concluded the Oxford scientists’ paper, which was published in the journal Science two months later.

The Oxford researchers believed a smartphone app could help locate individuals who didn’t know they were infected — and by alerting them quickly could reduce and even halt the epidemic if enough people used it. Within days of the meeting, NHSX began the process of awarding millions of dollars worth of no-bid contracts to develop such an app, government procurement records show.

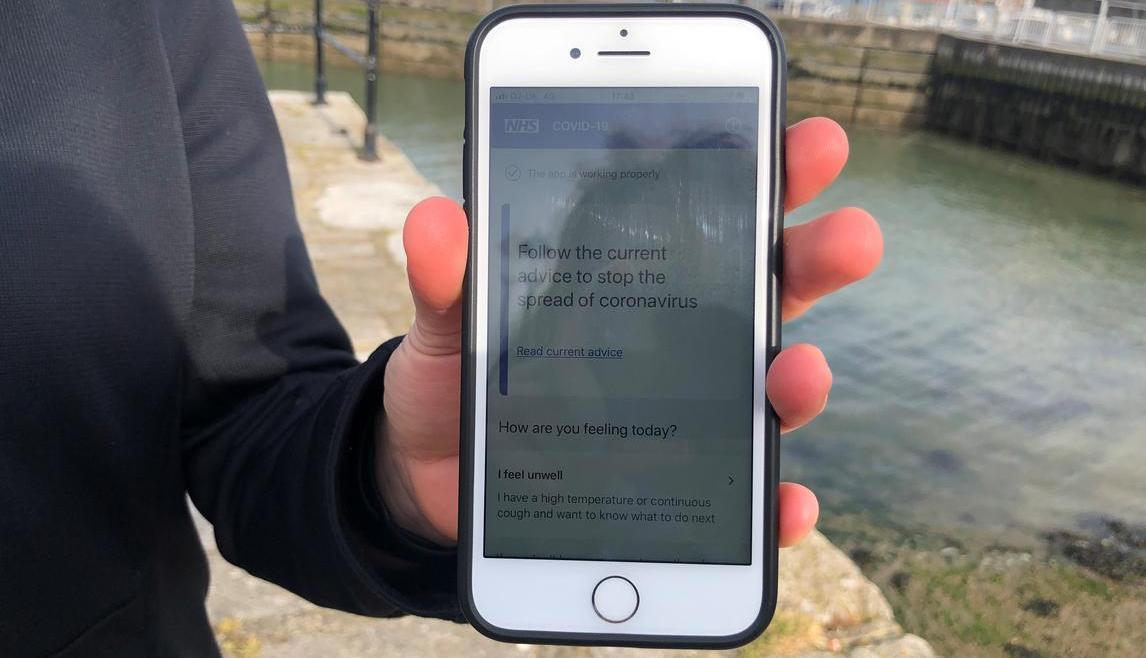

In the weeks that followed, ministers seized on the technology as a route out of Britain’s lockdown, which had begun on March 23. At a Downing Street coronavirus briefing on April 12, health secretary Matt Hancock announced that testing had begun on what he called the government’s “next step — a new NHS app for contact tracing.”

He explained people could use the app to report feeling unwell and it would anonymously alert other app users who had recently been in close contact with them. On April 28, he said he expected the app to be ready by mid-May.

Privately, some researchers who had proposed the app were dismayed that the government had stopped widespread testing on March 12, a decision they believed undermined the app’s effectiveness and public health in general. “We were very clear from the start that this thing needed to work with testing,” David Bonsall, a clinical scientist at Oxford who attended the March 7 meeting, told Reuters.

By early May, transport secretary Grant Shapps was heralding a test of the app on England’s Isle of Wight. “Later in the month, that app will be rolled out and deployed, assuming the tests are successful, of course, to the population at large,” he said. “This is a fantastic way to ensure that we are able to really keep a lid on this going forward.”

Pat Gelsinger, CEO of VMware, the Silicon Valley tech firm hired to develop the app, told a Fox Business television interviewer on May 8, “I tell you, we think this is the best one in the world, and we’re really thrilled to be working with the NHS in the U.K. to help bring it about.”

But by the end of May, government officials were downplaying the app. In an interview with Sky News, Hancock called the app “helpful,” but said traditional contact tracing needed to be rolled out first. Quoting another official, he said, “It puts the cherry on the cake but isn’t the cake.”

Behind the scenes, NHSX testers were discovering serious technical problems.

The agency had opted to develop an app that collected and stored data on central servers that could be used by health authorities and epidemiologists to study the disease. It relied on a technology called Bluetooth to determine who had recently been near someone displaying symptoms and for how long.

NHSX testers were finding that while the app could detect three-quarters of nearby smartphones using Google’s Android operating system, it sometimes could only identify 4% of Apple iPhones, according to government officials. The problem was that, on Apple devices, the app often couldn’t utilize Bluetooth because of a design choice by Apple to preserve user privacy and prolong battery life.

The issue was no secret. Apple and Google had jointly announced in April that they would release a toolkit to better enable Bluetooth on contact tracing apps. But to protect user privacy, it would only work on apps that stored data on phones, not central servers. The NHSX app didn’t work that way.

The government insisted it had developed a successful workaround to overcome the Apple issue. But not everyone was convinced. The advocacy group Privacy International, which had tested the app in early May, “found it wasn’t working properly on iPhones,” Gus Hosein, the group’s executive director, told Reuters. But because of the government’s assurances, he said, “We just assumed we were doing something wrong.”

Other countries, including Germany, decided they would change their apps to work with the Apple-Google toolkit. That raised another problem with the U.K. app — it likely wouldn’t be compatible with many other contact tracing apps, so British travelers wouldn’t be notified if they were exposed to the virus.

On June 18, weeks after the U.K. app was supposed to be rolled out, government officials announced a dramatic U-turn — they would abandon the app being tested on the Isle of Wight and try to create one that worked with the Apple-Google technology. Work had already begun on it, and they had learned lessons from the test, they said.

NHSX referred questions about the app to the health department, which said, “Developing effective contact tracing technology is a challenge facing countries around the world, and there is currently no solution that is accurate enough on estimating distance, identifying other users, and calculating duration, which are all required for contact tracing.”

A spokesperson for VMware said it “is proud of the work we have done and continue to do to rapidly develop an application to support the U.K.’s contact tracing and testing efforts.”

A government official expressed confidence the app would be ready by the autumn or winter — although initially, the official said, it might not contain contact tracing at all, but offer other services that are yet to be determined.

(Reporting by Steve Stecklow, edited by Janet McBride.)