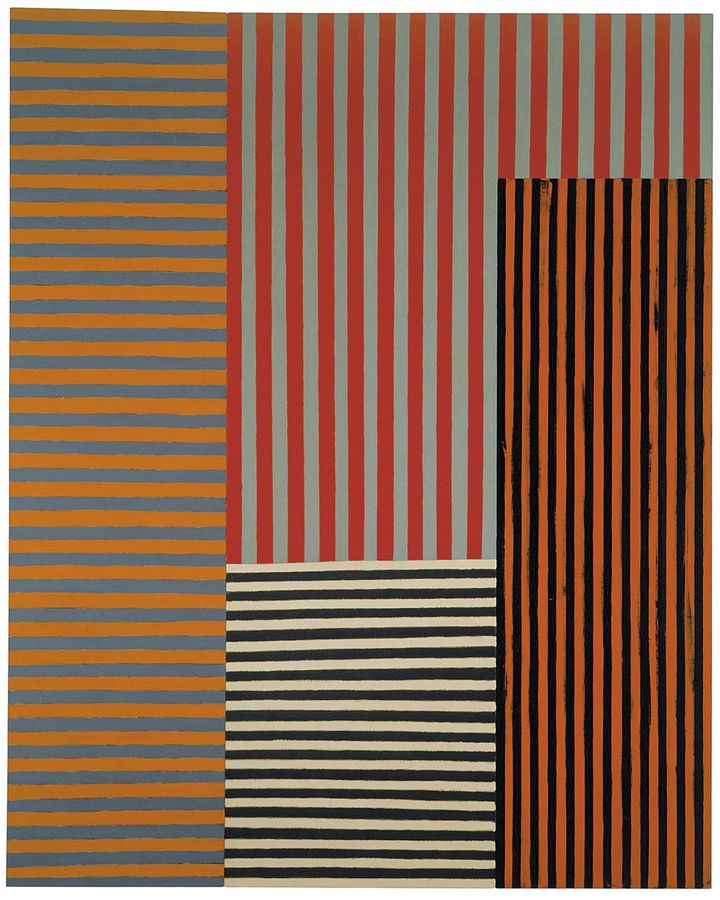

Some great works of art give us symbols to decode. Others decode us. Sean Scully’s Backs and Fronts, an enormous 20-foot-long, 11-panel painting of strident stripes and raucous rhythms that thrums beyond the borders of itself, is one of those. It changed the course of art history in the early 1980s by restoring to abstract painting a dimension it had lost – its capacity for intense feeling. Last year, when global lockdowns were forcing the world to look inside itself, I spent dozens of hours on the phone with the Irish-American artist, now in his 70s, discussing everything from his homeless infancy on the streets of Dublin in the 1940s to how he came to create one of the most important works of the past half century – a work widely credited with rescuing abstract art from the brink of irrelevance.

More like this:

– The mystery of the ‘lost Leonardo’

– Why Disneyland is an art masterpiece

– Will there be a new ‘Roaring 20s’?

What emerged from those conversations with Scully – whom the legendary art critic and philosopher Arthur Danto once described as “an artist whose name belongs on the shortest of short lists of major painters of our time” – is an unexpectedly inspirational tale of personal struggle, resilience, and creative triumph. The soulful stripes and bricks of battered colour that have come to define Scully’s visual language in the decades since the watershed creation of Backs and Fronts in 1981 are anything but coldly calculated, meticulously mathematical, or emotionally inert. Scully’s canvases are loaded not only with a profound understanding of the history of image-making – from Titian’s command of colour to the way Van Gogh consecrates space – but with the mettle of a life that has weathered everything from abject poverty, to the death of his teenage son (who was killed in a car accident when the painter was in his 30s), to the envious resistance of a critical cabal in New York that begrudged his achievements. Time and again, art has proved Scully’s salvation.