Economy

Biden will have a long list of economic fixes to make: Experts say these are the top 3 – NBC News

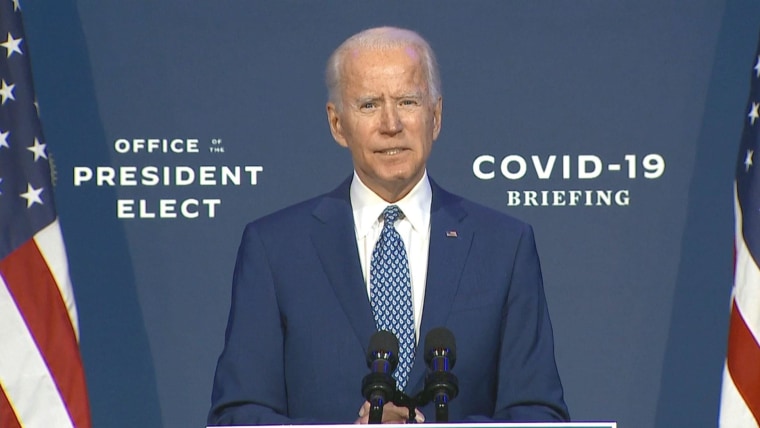

Economists and market analysts say that when President-elect Joe Biden takes the oath of office in January, he will inherit a battered economy. While most metrics of economic activity have risen from the record-shattering lows they hit in March and April, the pace of improvement has slowed, and analysts worry that burgeoning Covid-19 case numbers will throttle the hard-won economic momentum the country has eked out so far.

It won’t be easy. Control of the Senate is still up in the air, but many believe it’s likely that Congress’s upper chamber might still have have a Republican majority with Sen. Mitch McConnell, R-Ky, as Majority Leader. Although Biden has referenced his work with McConnell in the past to bolster his credentials as a politician who can successfully work across the aisle, McConnell’s public backing of President Donald Trump’s refusal to concede on Monday was, if nothing else, a clear indication that bipartisanship will be elusive for Biden.

“With a divided Congress, a handful of the major legislative priorities of a Biden administration seem unlikely,” said Ross Mayfield, an investment strategy analyst at Baird. “Any kind of major corporate tax hike or wealth tax seems incredibly unlikely with a Republican Senate.”

“Pfizer’s progress towards a vaccine is promising, but does not negate the need for lawmakers to act in the near term.”

Despite Biden positioning himself as a centrist, economists aren’t expecting much across-the-aisle cooperation. After a stimulus deal is passed, “I think it’s going to be difficult to do much beyond that, legislatively,” said Mark Zandi, chief economist at Moody’s Analytics.

Although Biden will be unable to put most of his — and his party’s — boldest initiatives into action, Zandi said the new president would likely implement a flurry of executive orders, many targeted at undoing policies Trump had unilaterally imposed the same way. “Biden’s going to reverse Trump on trade, on immigration, on climate change, on banking regulations,” he said. “It’s not big, fundamental shifts… it’s more incremental.”

Economists say these are the week-one, day-one challenges Biden will face as soon as he is sworn in — and how he might be able to meet them.

Corral the coronavirus

Although a public health crisis first and foremost, experts agree that containing and lowering the burgeoning number of Covid-19 cases is the only way to alleviate the economic crisis that has gripped the country since March. Getting the virus under control will ensure that stores, restaurants, hotels and entertainment venues can stay open, and that Americans will have the confidence — and the disposable income — to take flights, attend ball games, eat out at restaurants and shop in stores.

“He’s going to encourage the governors to recommend that face masks be mandatory in order to try and improve the chance of the economy opening as quickly as possible,” said Sam Stovall, chief investment strategist at CFRA Research. “I think everybody realizes that more action is needed.”

His administration will need to invest in people, equipment and technology to improve the availability and accuracy of testing, production and dissemination of PPE and development of virus-mitigation and contract tracing protocols — all goals endorsed by public health officials. However, observers caution that Biden could run into resistance from Republican Congress members and governors over issues such as mask mandates and increased funds for testing and contact tracing.

Get America more stimulus

Congress was unable to come to an agreement on the terms of a stimulus package before the election. Economists are divided on whether or not — and when — another tranche of aid might be forthcoming. “Any kind of coronavirus fiscal stimulus legislation still seems likely, [but] some of the good recent economic data shows economic momentum that has pared the appetite for a big bill,” Mayfield said.

Most analysts, along with top officials like Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell, do agree that additional stimulus is needed. The progress announced by Pfizer on Monday towards a Covid-19 vaccine was promising, some said, but did not negate the need for lawmakers to act in the near term.

“Regardless of the path of the virus, I think there’s pretty high awareness across the partisan spectrum that there needs to be some sort of bill to carry this recovery across the finish line,” Mayfield said.

A worsening public health picture could incentivize lawmakers to work quickly, some said. “Majority Leader McConnell’s reluctance to move ahead with a relief bill the last few months suggests it will be uphill sledding — though one might note that many experts expect the pandemic to be considerably worse by the time Biden is sworn in, which may make the politics of a broad relief and recovery effort somewhat more feasible,” said Mason B. Williams, a political science professor at Williams College.

Bring back jobs

A growing number of job losses are shifting from temporary to permanent, an ominous change labor economists say will get worse between now and the inauguration, particularly if the current alarming trajectory of case growth continues unchecked.

Economists agree that, even if a Biden White House is able to get a sufficient handle on Covid-19 to avoid reimposition of shutdowns, Americans will need the means as well as the willingness to spend. Securing more stimulus is an important first step, Stovall said. “He would want to focus on stimulus right away to save as many jobs as he can,” he said. With consumer spending the biggest contributor to GDP, putting money in the pockets of ordinary Americans is a quick way to insulate the jobs of countless cashiers, cooks, hairstylists, hotel staffers and others in high-contact service-sector positions.

Mayfield said another way Biden could contribute to job gains would be to coordinate more PPE production at American factories. “I think you’ll probably see some effort on some things like utilizing the Defense Production Act to mobilize some U.S. manufacturing,” he said. This would have a multifaceted impact touching on a few different Biden administration priorities: Adding jobs, securing enough PPE to combat Covid-19 and revitalizing American manufacturing with an eye towards rebuilding.

“In proposing a Public Health Jobs Corps, Biden is wisely copying from the New Deal’s playbook of providing short-term ‘emergency’ employment.”

Biden’s transition website calls for establishing a 100,000-person job corps to combat the coronavirus. “In proposing a Public Health Jobs Corps, Biden is wisely copying from the New Deal’s playbook of providing short-term ‘emergency’ employment in ways that will stimulate long-term economic growth,” Williams said.

Although hailed by some as a proactive way to tackle the nation’s considerable public health as well as economic challenges, this proposal would likely face resistance from Congressional Republicans. Likewise, Biden’s proposals to develop jobs in sectors as diverse as infrastructure, green energy and child- and elder-caregiving all would require the kind of spending outlays he would be unlikely to wrest from a GOP-led Senate.

“Republican Senators are even less likely to support Biden’s spending priorities than they would be likely to support some of Trump’s spending priorities,” said Chris Zaccarelli, chief investment officer for the Independent Advisor Alliance.

Economy

What to read about India's economy – The Economist

AS INDIA GOES to the polls, Narendra Modi, the prime minister, can boast that the world’s largest election is taking place in its fastest-growing major economy. India’s GDP, at $3.5trn, is now the fifth biggest in the world—larger than that of Britain, its former colonial ruler. The government is investing heavily in roads, railways, ports, energy and digital infrastructure. Many multinational companies, pursuing a “China plus one” strategy to diversify their supply chains, are eyeing India as the unnamed “one”. This economic momentum will surely help Mr Modi win a third term. By the time he finishes it in another five years or so, India’s GDP might reach $6trn, according to some independent forecasts, making it the third-biggest economy in the world.

But India is prone to premature triumphalism. It has enjoyed such moments of optimism in the past and squandered them. Its economic record, like many of its roads, is marked by potholes. Its people remain woefully underemployed. Although its population recently overtook China’s, its labour force is only 76% the size. (The percentage of women taking part in the workforce is about the same as in Saudi Arabia.) Investment by private firms is still a smaller share of GDP than it was before the global financial crisis of 2008. When Mr Modi took office, India’s income per person was only a fifth of China’s (at market exchange rates). It remains the same fraction today. These six books help to chart India’s circuitous economic journey and assess Mr Modi’s mixed economic record.

Breaking the Mould: Reimagining India’s Economic Future. By Raghuram Rajan and Rohit Lamba. Penguin Business; 336 pages; $49.99

Before Mr Modi came to office, India was an unhappy member of the “fragile five” group of emerging markets. Its escape from this club owes a lot to Raghuram Rajan, who led the country’s central bank from 2013 to 2016. In this book he and Mr Lamba of Pennsylvania State University express impatience with warring narratives of “unmitigated” optimism and pessimism about India’s economy. They make the provocative argument that India should not aspire to be a manufacturing powerhouse like China (a “faux China” as they put it), both because India is inherently different and because the world has changed. India’s land is harder to expropriate and its labour harder to exploit. Technological advances have also made services easier to export and manufacturing a less plentiful source of jobs. Their book is sprinkled with pen portraits of the kind of industries they believe can prosper in India, including chip design, remote education—and well-packaged idli batter. Both authors regret India’s turn towards tub-thumping majoritarianism, which they think will ultimately inhibit its creativity and hence its economic prospects. Nonetheless this is a work of mitigated optimism.

New India: Reclaiming the Lost Glory. By Arvind Panagariya. Oxford University Press; 288 pages

This book provides a useful foil for “Breaking the Mould”. Arvind Panagariya took leave from Columbia University to serve as the head of a government think-tank set up by Mr Modi to replace the old Planning Commission. The author is ungrudging in his praise for the prime minister and unsparing in his disdain for the Congress-led government he swept aside. Mr Panagariya also retains faith in the potential of labour-intensive manufacturing to create the jobs India so desperately needs. The country, he argues in a phrase borrowed from Mao’s China, must walk on two legs—manufacturing and services. To do that, it should streamline its labour laws, keep the rupee competitive and rationalise tariffs at 7% or so. The book adds a “miscellany” of other reforms (including raising the inflation target, auctioning unused government land and removing price floors for crops) that would keep Mr Modi busy no matter how long he stays in office.

The Lost Decade 2008-18: How India’s Growth Story Devolved into Growth without a Story. By Puja Mehra. Ebury Press; 360 pages; $21

Both Mr Rajan and Mr Panagariya make an appearance in this well-reported account of India’s economic policymaking from 2008 to 2018. Ms Mehra, a financial journalist, describes the corruption and misjudgments of the previous government and the disappointments of Mr Modi’s first term. The prime minister was exquisitely attentive to political threats but complacent about more imminent economic dangers. His government was, for example, slow to stump up the money required by India’s public-sector banks after Mr Rajan and others exposed the true scale of their bad loans to India’s corporate titans. One civil servant recounts long, dull meetings in which Mr Modi monitored his piecemeal welfare schemes, even as deeper reforms languished. “The only thing to do was to polish off all the peanuts and chana.”

The Billionaire Raj: A Journey Through India’s New Gilded Age. By James Crabtree. Oneworld Publications; 416 pages; $7.97

For a closer look at those corporate titans, turn to the “Billionaire Raj” by James Crabtree, formerly of the Financial Times. The prologue describes the mysterious late-night crash of an Aston Martin supercar, registered to a subsidiary of Reliance, a conglomerate owned by Mukesh Ambani, India’s richest man. Rumours swirl about who was behind the wheel, even after an employee turns himself in. The police tell Mr Crabtree that the car has been impounded for tests. But he spots it abandoned on the kerb outside the police station, hidden under a plastic sheet. It was still there months later. Mr Crabtree goes on to lift the covers on the achievements, follies and influence of India’s other “Bollygarchs”. They include Vijay Mallya, the former owner of Kingfisher beer and airlines. Once known as the King of Good Times, he moved to Britain from where he faces extradition for financial crimes. Mr Crabtree meets him in drizzly London, where the chastened hedonist is only “modestly late” for the interview. Only once do the author’s journalistic instincts fail him. He receives an invitation to the wedding of the son of Gautam Adani. The controversial billionaire is known for his close proximity to Mr Modi and his equally close acquaintance with jaw-dropping levels of debt. The bash might have warranted its own chapter in this book. But Mr Crabtree, unaccustomed to wedding invitations from strangers, declines to attend.

Unequal: Why India Lags Behind its Neighbours. By Swati Narayan. Context; 370 pages; $35.99

Far from the bling of the Bollygarchs or the ministries of Delhi, Swati Narayan’s book draw son her sociological fieldwork in the villages of India’s south and its borderlands with Bangladesh and Nepal. She tackles “the South Asian enigma”: why have some of India’s poorer neighbours (and some of its southern states) surpassed India’s heartland on so many social indicators, including health, education, nutrition and sanitation. Girls in Bangladesh have a longer life expectancy than in India, and fewer of them will be underweight for their age. Her argument is illustrated with a grab-bag of statistics and compelling vignettes: from abandoned clinics in Bihar, birthing centres in Nepal, and well-appointed child-care centres in the southern state of Kerala. In a Bangladeshi border village, farmers laugh at their Indian neighbours who still defecate in the fields. She details the cruel divisions of caste, class, religion and gender that still oppress so many people in India and undermine the common purpose that social progress requires.

How British Rule Changed India’s Economy: The Paradox of the Raj. By Tirthankar Roy. Springer International; 159 pages; $69.99

Many commentators describe the British Empire as a relentless machine for draining India’s wealth. But that may give it too much credit. The Raj was surprisingly small, makeshift and often ineffectual. It relied too heavily on land for its revenues, which rarely exceeded 7% of GDP, points out Tirthankar Roy of the London School of Economics. It spent more on infrastructure and less on luxuries than the Mughal empire that preceded it. But it neglected health care and education. India’s GDP per person barely grew from 1914 to 1947. Mr Roy reveals the great divergence within India that is masked by that damning average. Britain’s “merchant Empire”, committed to globalisation, was good for coastal commerce, but left the countryside poor and stagnant. Unfortunately, for the rural masses, moving from rural areas to the city was never easy. Indeed, some of the social barriers to mobility that Mr Roy lists in this book about India’s economic past still loom large in books about its future.

Also try

We regularly publish special reports on India, the latest, in April 2024, focuses on the economy. Please also subscribe to our weekly Essential India newsletter, to make sure you don’t miss any of our comprehensive coverage of the country’s economy, politics and society.

Economy

The Fed's Forecasting Method Looks Increasingly Outdated as Bernanke Pitches an Alternative – Bloomberg

The Federal Reserve is stuck in a mode of forecasting and public communication that looks increasingly limited, especially as the economy keeps delivering surprises.

The issue is not the forecasts themselves, though they’ve frequently been wrong. Rather, it’s that the focus on a central projection — such as three interest-rate cuts in 2024 — in an economy still undergoing post-pandemic tremors fails to communicate much about the plausible range of outcomes. The outlook for rates presented just last month now appears outdated amid a fresh wave of inflation.

Economy

Slump in Coal Production Drags Down Poland’s Economic Recovery

|

|

A 26% plunge in coal mining weighed on Poland’s industrial output in March 2024, casting a shadow over the expectations that the biggest emerging-market economy in Europe would grow by the expected 3% this year.

Coal mining output slumped by 25.9% year-over-year in March, contributing to a 6% decline in Poland’s industrial production last month, government data showed on Monday. This was the steepest decline in Poland’s industrial output since April 2023, per Bloomberg’s estimates. It was also much worse than expectations of a 2.2% drop in industrial production.

The steep drop in the Polish industry last month raises questions about whether the EU’s most coal-dependent economy would manage to see a 3% rebound in its economy this year, as the central bank and the finance ministry expect.

Still, it’s too early into the year to raise flags about Poland’s economy, Grzegorz Maliszewski, chief economist at Bank Millennium, told Reuters.

“I wouldn’t radically change my expectations here, because there are many reasons to expect a continuation of economic recovery, as domestic demand will increase and the economic situation in Germany is also improving,” Maliszewski said.

Meanwhile, Poland’s new government has signaled it would be looking to set an end date for using coal for power generation, a senior government official said.

“Only with an end date we can plan and only with an end date industry can plan, people can plan. So yes, absolutely, we will be looking to set an end date,” Urszula Zielinska, the Secretary of State at the Ministry of Climate and Environment, said in Brussels earlier this year.

Last year, renewables led by onshore wind generated a record share of Poland’s electricity—26%, but coal continued to dominate the power generating mix, per the German research organization Fraunhofer Society.

Poland’s power grid operator said last month that it would spend $16 billion on upgrading and expanding its power grid to accommodate additional renewable and nuclear capacity.

-

Business12 hours ago

Honda to build electric vehicles and battery plant in Ontario, sources say – Global News

-

Science13 hours ago

Science13 hours agoWill We Know if TRAPPIST-1e has Life? – Universe Today

-

Investment16 hours ago

Down 80%, Is Carnival Stock a Once-in-a-Generation Investment Opportunity?

-

Health13 hours ago

Health13 hours agoSimcoe-Muskoka health unit urges residents to get immunized

-

News18 hours ago

Honda expected to announce multi-billion dollar deal to assemble EVs in Ontario

-

Sports23 hours ago

Sports23 hours agoJets score 7, hold off Avalanche in Game 1 of West 1st Round – NHL.com

-

Science18 hours ago

Science18 hours agoWatch The World’s First Flying Canoe Take Off

-

Art23 hours ago

‘Luminous’ truck strap artwork wins prestigious Biennale prize in first for New Zealand – The Guardian