The inaugural Starliner test flight didn’t go according to plan, but it still made a little bit of history. Boeing’s spacecraft landed safely at New Mexico’s White Sands Missile Range at 7:58AM Eastern, making it the first US-made, crew-ready capsule to touch down on solid ground. Previous capsules from the Mercury, Gemini and Apollo programs all landed in the sea. This capsule didn’t have any humans aboard (the test dummy Rosie doesn’t count), but this is still a watershed moment.

Science

Boeing Starliner is the first US-made crew capsule to land on the ground – Engadget

Starliner didn’t dock with the International Space Station as planned, but it still collected ample amounts of data across the flight, including Rosie’s insights as to how humans would fare during a trip. The team likely collected about 85 to 90 percent of what they were looking for, Boeing’s Jim Chilton said during a post-touchdown briefing. The mission team previously said it was confident it could fix the mistake that prevented the docking.

Just what happens next is uncertain. Boeing and NASA said during the briefing that they still expected a crewed flight in 2020, but that they wanted to review data before deciding the next course of action. There are still more dry runs to go, including an in-flight abort test to complement the launch abort test from November. While NASA is eager to reduce its dependence on Russian spacecraft to transport astronauts, it also wants to ensure that vehicles like Starliner and SpaceX’s Crew Dragon are trustworthy before there are people aboard.

LANDING CONFIRMED

The #Starliner spacecraft safely touched down at 7:58am ET at @WSMissileRange in New Mexico with a bulleye landing. This marks the 1st time an American-made, human-rated capsule has landed on land. Watch our live coverage: https://t.co/MAYPLDF7R7 pic.twitter.com/66owuQDsVB

— NASA (@NASA) December 22, 2019

Science

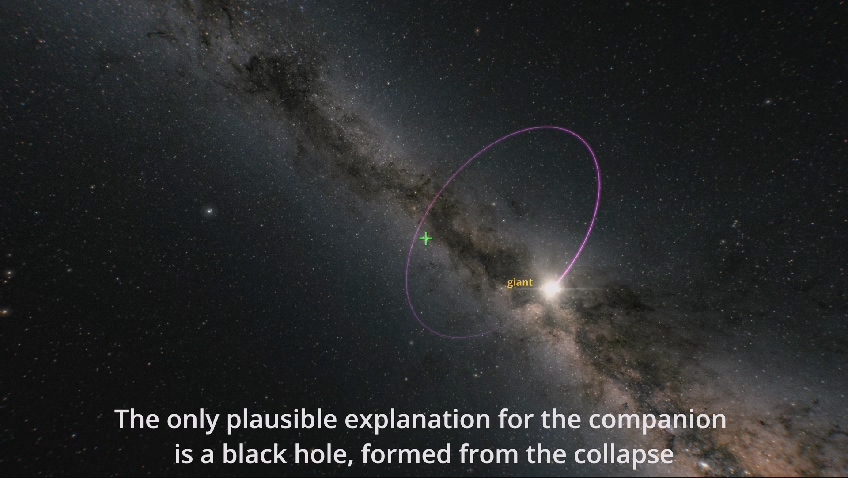

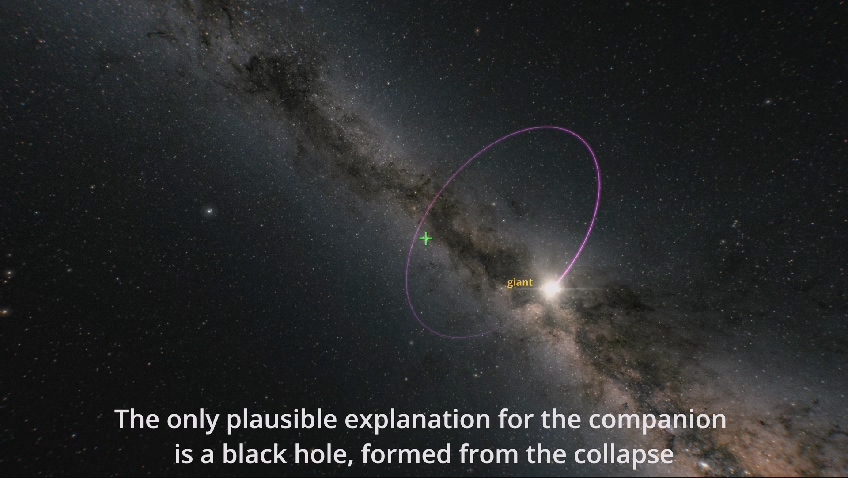

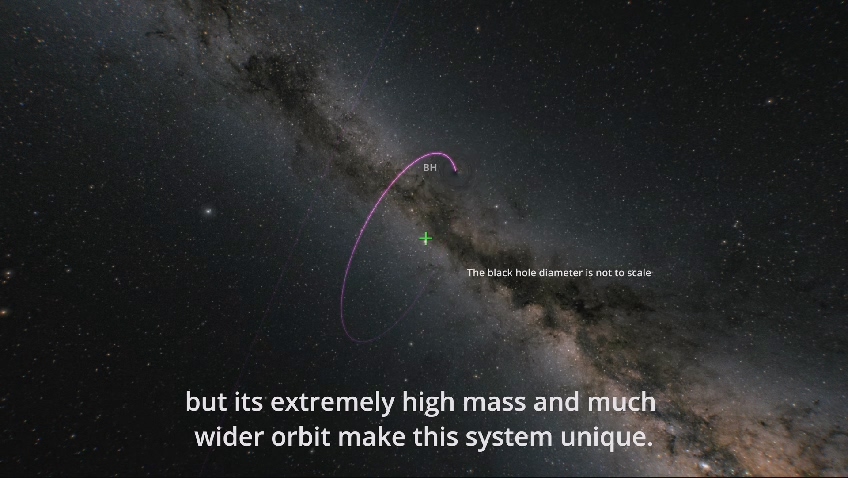

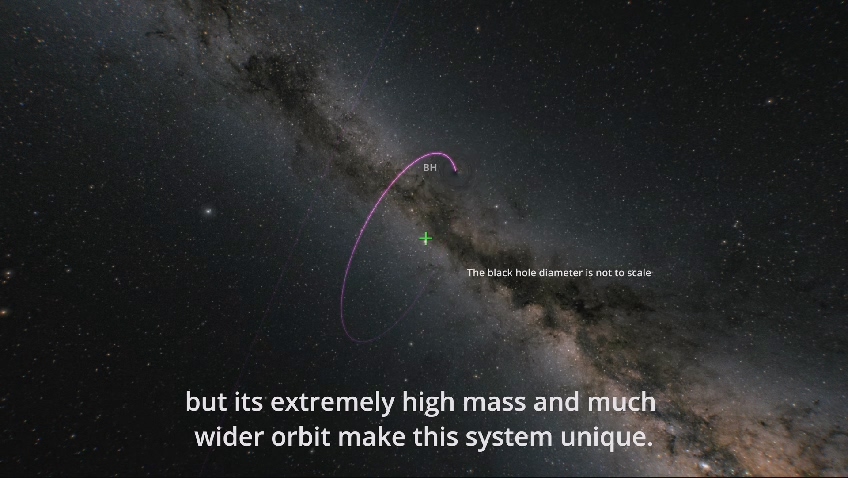

Astronomers discover Milky Way's heaviest known black hole – Xinhua

JERUSALEM, April 16 (Xinhua) — Astronomers have found BH3 is by far the heaviest known stellar black hole in the Milky Way galaxy, 33 times the mass of the Sun.

An international research team found the black hole when looking into the latest data group recorded in the European Space Agency’s Gaia space telescope, Israel’s Tel Aviv University (TAU) said in a statement on Tuesday.

The black hole is located 1,500 light-years away from Earth, said TAU, whose researchers participated in the study of the newly discovered binary system.

In binary systems, a visible star can be found orbiting a massive but unseen companion, indicating the latter is a black hole.

Binaries have revealed around 50 suspected or confirmed stellar-mass black holes in the Milky Way, but scientists think there may be as many as 100 million in our galaxy alone, according to NASA.

Stellar-mass black holes are formed when a star runs out of its nuclear combustion fuel and collapses.

The massive black hole BH3 was detailed in the open-access journal Astronomy & Astrophysics for further study.

Science

'Almost hit my son' – Space junk crashes through Florida home – BBC.com

“It almost hit my son” – three years ago the International Space Station threw out refuse into space, expecting it to undergo “a natural re-entry”.

But a heavy piece of debris crashed through a home in Naples, Florida, narrowly missing the householder’s son.

Science

Solar eclipse on April 8 dazzles sky watchers across Quebec

-

Sports11 hours ago

Sports11 hours agoTeam Canada’s Olympics looks designed by Lululemon

-

Real eState19 hours ago

Search platform ranks Moncton real estate high | CTV News – CTV News Atlantic

-

Tech18 hours ago

Motorola's Edge 50 Phone Line Has Moto AI, 125-Watt Charging – CNET

-

Science22 hours ago

Science22 hours agoSpace exploration: A luxury or a necessity? – Phys.org

-

Science24 hours ago

SFU researchers say ant pheromones could help prevent tick bites – Global News

-

Sports22 hours ago

Sports22 hours agoRECAP: Red Wings' 5-4 comeback OT victory against Canadiens the result of belief, resiliency | Detroit Red Wings – NHL.com

-

News20 hours ago

Former mayor appealing sexual assault conviction dies of cancer

-

Politics22 hours ago

Politics22 hours agoLiz Truss backs Donald Trump to win US presidential election – BBC.com